Over the decades I have met many people who tell me they are from Chicago. In fact, most of them are not truly from Chicago, but from the neat and tidy suburbs outside the city. Unlike them my brother, Don, and I were raised inside the city limits of Chicago, in a neighborhood known as "North Center,"located on Chicago's "North Side."

Here's where it all began. Excepting a two-year stint in military school, until around the ages of ten and eleven Don and I lived in this apartment building at 3825 Lincoln Avenue. The two 2nd story windows directly above the SUV seen here mark the apartment in which we lived during the '40s and early '50s. Because the building was steam heated, the windows were often caked during the winter with thick ice that obscured the view of the street, but to our delight the frosted glass dramatically enhanced the dazzling green and blue flashes produced by electric trolley cars that once passed by on the street below.

Typical model of streetcar that traveled in front of our apartment on Lincoln Avenue in Chicago during the 1940s.

This is our mother, Molly Groh. The grotesque homunculus on the right is my brother, Don. I always felt that there was something seriously wrong with Don; I still do. I think he was left on our doorstep by Martians. The attractive kid on the left, with the face expressing wisdom beyond his years — that's me. Ours was a German family, one amongst a multitude of other Germans living on Chicago's North Side during World War II, when America was at war with Germany. We had to walk softly back then. Our mother had a strong-willed and volatile personality. Our father, easy-going and strongly disinclined to confrontation. Doomed to fail, their marriage ended after only eight years. The picture above was taken in 1946, on Berniece Street, on our apartment building's northwest corner.

This is the same spot, on Bernice Street, as it appears now (October 2005). At the far end of this brick wall is a driveway that leads to a small, cramped courtyard situated in the center of the apartment building.

This small alley was used by coal trucks to reach the coal chute (glass block window at pavement level) used to convey coal to the building's basement furnace. The alley also leads to the building's courtyard, where Don and I played as kids. Behind the fence in the background was our "baseball field."

This parking lot, now paved over, used to be surfaced only with gravel and dumpsters didn't exist in the '40s and '50s, only "ash cans." I spent many scorching, hot summer days here with other kids in the neighborhood playing impromptu games of "Bounce or Fly." Today, kids seem mostly herded (for their own good) into playing "organized" baseball. I think that's sad - they don't know what they're missing.

This is our apartment building's charming courtyard. The windows at ground level face into the basement where our mother did the laundry. One day, while playing in the basement, my brother got his hand caught in the washing machine's wringer. By the time I reached him it had taken his arm all the way to the elbow. I didn't know the ringer had an emergency release, so I just put the rollers in reverse and wrung his arm back out! Don says it hurt.

Washboard and old-fashioned wringer washing machine of the sort we had in the '40s and '50s.

The courtyard, seen from the opposite end today. Forty-five years later, Don stands in front of the staircase leading to the rear of our old apartment. We used to play under this staircase in the summer during thunderstorms. Here, our play space is used as a dump site for abandoned furniture

.

Here, at the top of the stairs, is our old apartment's back door. To the immediate right is a fenced off portion of a small roof that extends over a storeroom on the ground floor.

This roof is adjacent to our old bedroom window, through which we would often climb so many years ago to go sunbathing with our mother.

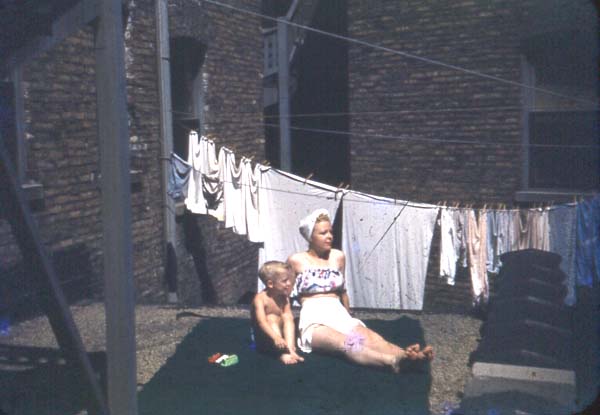

The 1940s. Clotheslines laden with drying laundry crisscrossed the space above the courtyard. On this sunny day, Don joined our mother for a tan. We were both fair-skinned, and trips to Montrose Beach often resulted in terrible, 2nd degree sunburns that left us badly blistered and in agony for days. In the fall of 2008 Don was diagnosed with a case of melanoma. Fortunately, it was caught in time.

Our neighborhood was a light, industrial area. The factory in the foreground is located around the corner from our apartment building, at the end of the block. Forty-five years later it still stands, but has been converted to residential "lofts." Between it and the foreground is the railroad embankment Don and I used to climb so we could get close to the rails and thrill at the sight of the massive wheels and driving rods of steam locomotives that belched voluminous clouds of smoke as they thundered by.

A Chicago elevated train, or "L." Under these L tracks, this factory once stored huge, steel tubs. Don and I used to play here, and on one occasion crawled about the insides of a large pile of such tubs. After our clothing dissolved we decided it was not such a great idea to play there anymore. In the distance is another factory which was used by the Speed-O-Print Business Machines Corporation.

This is a classic example of the back-porch architecture common to apartment buildings of the Chicago we knew as children. Despite the passage of more than a half century, this feature of the city remains unchanged. These porches face an alley through which Don and I walked countless times as we traveled between our apartment building and our grandmother's house on Larchmont Street, three blocks away.

The house on the right, 1910 Larchmont, was our grandmother's home. It was located just three blocks from our apartment building. In the 1940s it was virtually identical to the house on the left. Back then meals were cooked on a wood-burning kitchen stove.

Three doors down from my grandmother's house was the home of a Jewish family, the Karens. My family had been broken by divorce, and with neither parent taking responsibility for me, I eventually found myself on the verge of homelessness. The Karens generously took me in and raised me almost as if I were their own. Although I attended Catholic schools , I eventually came to think of myself as Jewish. After my experiences with violent death while in the army, I beganto question all I had been taught as a child about religion and soon abandoned my beliefs in the supernatural. Nevertheless, years later, with the help of an understanding Rabbi working at a Hillel Foundation office at my university, I converted to Judaism, not out of a need to worship a god, but to find my place among a people and a culture into which I had become assimilated. If I thought there truly were a benevolent god, I would demand that it bestow justly deserved happiness upon Saul, Bob, Eileen, and most especially, upon my Jewish mother, dear, caring Esther.

When we were small our parents sometimes took my brother and me to this marvelously paradoxical Chinese restaurant, the "Orange Garden." The sign over the entrance is older than I am. Back in the '40s the Orange Garden served not only "chop suey," but in addition, another great neighborhood favorite — "spaghetti and meatballs!" I was told by the owner during my visit in 2005 that they served whatever the neighborhood's residents would eat. I ate my last serving of spaghetti and meatballs at the Orange Garden in 1960.

Only 5 blocks from where we lived stands this factory where, during one period in her tempestuous life, my mother once worked. Below the "L" tracks in the foreground, fixed to a railroad viaduct well behind, is a large sign reading, "A Sensation." It seems an ironic comment on a life of misfortune unhappiness that ran its course here so long ago. Our mother, Molly Groh, died several days after a motor vehicle accident in 1967.

Andes Candies, Pete Gochey's Market, Carr's Grocery, Eddie Fowler's Butcher Shop, Zip's Poultry, George and Grace's Truck Stop, Heinz Lumber — all the neighborhood businesses I once knew are now gone, save three. This one, "Stauber's Hardware," has been around longer than I have (I'm 70 now). I remember this store on Lincoln Ave having an uncommonly creaky, wooden floor. Today that floor is covered with linoleum, but when I walked on it during my visit, it once again spoke to me, through its linoleum cover, in those same, familiar creaks and squeaks that I remember from childhood.

In the early '50s my brother got his very first job at Stauber's Hardware. Here is his story:

"I walked into Stauber's Hardware one summer afternoon and saw this neat Schwinn bicycle hanging on the wall. I knew that Mom could never afford to buy it, so I asked a clerk who, as it turned out was Mr. Stauber himself, if they needed any summer help. He briefly pondered my question and then replied in the affirmative. His answer made it plain enough to me that owning the bike was a possibility. He then told me that I would need my mother's permission because I was far below the age of employment. Excited, I went home and told Mom what had taken place. She grabbed her purse and away we went, back to the hardware store, to see the friendly clerk. As we entered the store Mr. Stauber greeted us and then stepped out of earshot with Mom. After speaking together a few moments they agreed that I would start work the next morning. I couldn't wait!

Morning couldn't come soon enough. When I awoke, the first thing I thought was that the bike in the hardware store soon would be mine. I dressed as fast as I could, skipped breakfast, ran out the door and got to the store before it opened. As I waited for my boss to show up I kept looking through the window and could see the bike that surely would be mine, still hanging on the wall. Finally, my first ever employer showed up and complimented me for being on time. "Ahhh," he said, "Just what I need at this time - brownie points." I knew this was good. I looked back again at MY bike hanging on the wall.

Mr. Stauber then led me down a flight of stairs to the basement and into a room that was apparently below sidewalk level, just next to the street. I drew this conclusion from the square glass block ceiling tiles that let sunlight into the room. Against the walls were rows of shelving that were stocked with boxes of door hardware: hinges, door knobs, lock sets, etc. Many of the boxes had been opened and their contents not properly returned. My job was to go through the boxes, compare their contents with the pictures of the items contained within each box and return misplaced items to their appropriate containers. This was an easy job for a kid of eight; my butt was already on the seat of that bike!

As I remember, I worked all day, never stopping for lunch or even to go to the bathroom. I finally stopped when deep shadows fell over the glass block ceiling, making it too dark to see the pictures on the boxes. There were no electric lights in this room. I figured my day's work was done.

I wondered to myself how many days it would take to earn my bike as I found my way back up to the first floor. Mr. Stauber smiled and asked how it went down in the "dungeon." I didn't know what he meant about a dungeon but I smiled back and replied that everything went fine. He then led me over to the sporting goods department and asked me what I would like for payment for my day's work. He said that I could pick out anything worth up to $3.00. Pointing to the Schwinn hanging on the wall, I told him my plan was to save up enough to buy the bike. He smiled and said that the job was only for one day, and because I was under age, I could not be paid in cash. As a consequence, he said, I could only pick out $3.00 worth of merchandise.

This was my very first job. It also turned out to be the very first time that I had felt truly betrayed. Reluctantly, I picked out $3.00 worth of stuff that I didn't really want: some fishing hooks, bobbers, and of all things — some jeweled, red bike reflectors. As I walked home from the very first, and shortest job of my life, I felt that the lesson to be learned from the day's experience was what it means to get "shafted." It was a hard lesson, but I put my disappointment behind me, knowing that this was only my first job. Others would be better, especially the pay part!

Don

After my visit to the old neighborhood I spent the next day downtown, in Chicago's