In the 1950s the Adler Planetarium was, to me, nothing short of "awesome," not as the term is used today to inflate the trivial, but as it was meant to be used — to describe that which inspires veneration and wonder. Admission was free when I was a boy, so on weekends I would often walk the 9 miles to the Adler from my home near Lincoln and Irving, on Chicago's North Side, using money I got from redeemed soda bottles to pay for "carfare" for the return trip home, and sometimes for a hot dog for lunch. Were I a kid again, I doubt I could do that today. Now, the price of admission to the Adler is $13. That's an awful lot of soda bottles! True, on Mondays and Tuesdays admission is now free, but only during the months when kids are in school. If there is anything about which I am entirely confident, it is my view that no youngster should ever —EVER — be barred from entry to the Adler, or any other museum for that matter, on account of money, most especially when he or she chooses to go there of his or her own volition!

When I was a kid, one of my very few heroes was a lecturer on the Adler's staff. At the conclusion of one of his planetarium shows I asked him to explain to me exactly how telescope lenses produced and magnified an image. Generously giving of his time, he took me into the planetarium's library, provided a couple of books for reference, and sat down with me at a table. Using pad and pencil, he carefully drew a series of diagrams that revealed the answers to what had been a frustrating riddle. Regrettably, I never learned the man's name. Now, nearly fifty years later, I often wonder if he ever had even the slightest notion as to how many people his generosity that day would eventually touch — how many lives would one day be saved because of his kind act.

The Adler Planetarium filled my life with wonder, fueled my imagination, and spurred me on to explore my potential. It inspired me to go on to college, study the sciences, and pursue a career in medical research that led to the significant role I played in the development of "two-dimensional, transesophageal, echocardiography," an intra-operative heart monitoring technology now used in operating rooms throughout the world.

It was in large measure the Adler Planetarium that inspired me

to study the sciences and pursue a career in medical research.

True, my chosen field was not astronomy, but the Adler was a highly significant influence in my life nonetheless. I owe both Mr. Adler and my unknown hero an enormous debt. I hope they would consider it paid, if not in full, then at least in its greater part. And, I wish that the countless individuals whose lives have been and will be saved by my contribution to medicine could know that it is to these two men, and the Adler Planetarium, that they are partially indebted.

Homecoming

In October of 2005, after a 45-year absence, I returned to the Adler Planetarium, hoping once again to find the excitement, the wonder, and the inspiration I knew as a young boy. I knew there would be changes and prepared myself to meet them. Sadly, it proved difficult for me to deal with some of what I found.

Millennium Adler

As I approached the Adler from a distance the first change I discovered was that a new structure partially surrounded and enclosed the original building. Named the "Sky Pavilion," the addition had been opened in 1999 to enhance revenues and expand the planetarium's museum, originally a circular corridor surrounding the exterior of the planetarium chamber. Originally, the corridor's walls had been hung with numerous, captivating photographic plates of astronomical objects taken by telescopes from around the world. The museum also had a lower level featuring exhibits that included a large meteorite one could touch, an impressive meridian telescope, a marvelous collection of astrolabes dating back to the 13th-century, and enormous representations of a solar eclipse and M 31, the "Great Galaxy in Andromeda," which were made to fluoresce with untraviolet lights. All of these were gone.

I must confess, I didn't particularly care for the look of the "Sky Pavilion" as I felt that it robbed the original structure of its unique, enticing appearance. Moreover, like the cracker box penthouses unceremoniously dumped atop Chicago's former Stevens Hotel, the architecture of the Adler add-on structure was, in my view, entirely out of concert with the Art Deco architecture of the original building. I believe Max Adler would have described both as chalushes!

Hilton Penthouses — The Work of an Architect, or an Assassin?

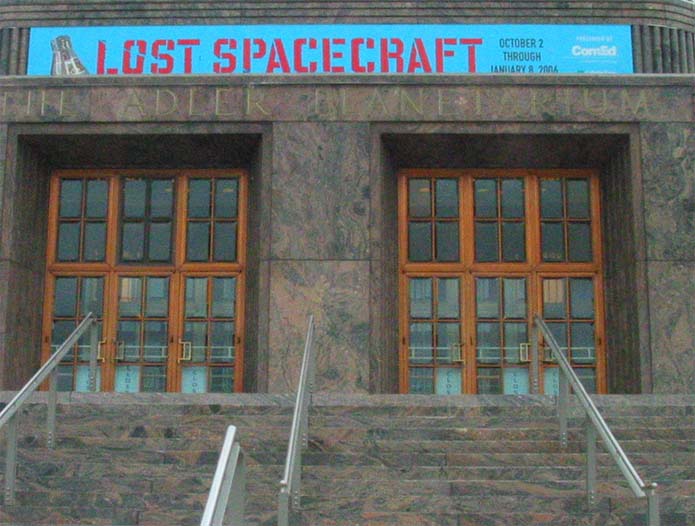

More disappointment was yet to come. As I approached

the planetarium's main entrance, this is what I saw.

Graffiti, By Any Other Name . . .

It saddened me greatly to see that the original building's splendid exterior had been plastered over with commercial advertising. Left of the entrance was a large banner announcing the institution's 75th anniversary. What was the point, I wondered? Would the banner be changed next year to read "Adler 76," the year after that to "Adler 77?" Could anyone possibly care? Was it really necessary to relegate forevermore this unique, architectural masterpiece to use as a billboard?

Panem et Circensus

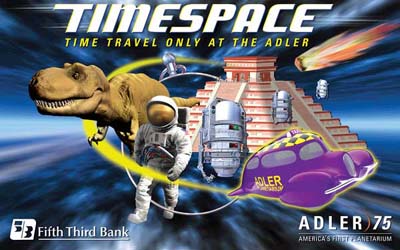

On the opposite side of the building a vulgar, cartoonish banner featured a dinosaur. "GRRR, GRRR, GRRR," it roared! On the upper right, a flaming meteor threatened to destroy a Mayan temple, with luck, maybe even the whole world! BOOM, BOOM, BOOM! "Time travel ONLY at the Adler," the banner boasted! Soon, I feared, a carny barker would leap out of a puff of smoke to shout, "Hu-rry, hu-rry, hu-rry! Step right up! See blood sacrifices by savage Indians! See T-Rex rip the spaceman to pieces! BALLS OF FIRE! See the whole universe explode and burn — over and over — again and again — and AGAIN!"

The handwriting was literally on the wall. The public's exposure to astronomy was destined to be moved to some forgotten catacomb beneath the streets of Chicago while, at the Adler, more lucrative spectacles would be conducted to gratify jaded masses. There, eyes would no longer turn upward toward the stars, but downward, toward bloody sands. The hushed auditorium once dedicated to the study of the heavens would soon reverberate with the roar of frenzied crowds crying, "Habet, peractum est!"

Lost in Space, or Lost in Purpose!

Two sets of magnificent doors, beautifully adorned with thick, beveled glass, still guarded the main entrance of the Adler. As a youth I saw them as sentinels, standing watch over a portal to the unknown. When I ascended the granite steps that rose to meet them I could almost hear them speak. "Herein lie the secrets and mysteries of the universe," they whispered! "Beyond lie wonders indescribable. Prepare for the unfathomable, tax your imagination, challenge your mind — and enter!"

Every time I approached those beckoning sentries I had been reassured that a grand adventure awaited. Never once had I been disappointed. Through the Adler's planetarium lectures I learned about the planets, the stars, constellations, galaxies, navigation, light refraction, declination, right ascension, orbital mechanics, comets, solar flares, gravity, meteors, cosmic radiation — the list was endless.

Now, a vulgar banner insolently demanding my complete attention surmounted those wondrous doors. Blue in color, it clashed violently with the hue of the surrounding stone. In gaudy, red letters it screamed, "LOST SPACECRAFT!"

The magical voice that once beckoned me to journey to the stars, that seductive whisper I longed to hear just one more time had been altogether drowned out.

Liberty Bell VII

Make no mistake! I was captivated by the idea of spaceflight when I was young. Literally risking life and limb, I climbed out on the roof of my grandmother's house to see Sputnik fly overhead in 1957.

My grandmother's house on Larchmont Street as it is today. From the right-hand window on the 2nd floor I ascended the roof to the very top to see Sputnik pass overhead in 1957.

While NASA was launching (and often blowing up) its first rockets, a schoolmate and I were building and launching our own, often with greater success. I followed Project Mercury in the news and was stunned by the US Navy's failure to retrieve Liberty Bell 7. Today, I support NASA's programs, thrill at photos coming back from probes to our solar system's planets, and hope desperately to be alive when news arrives of man's first landing on Mars. But, puh-lease! "Lost Spacecraft???" That's just a bit overdone, isn't it? The location of Liberty Bell 7 had been known, since the day it sank to the seafloor after it's return to earth. Moreover, thanks to the Adler's PR people there can scarcely be a soul alive who didn't know where it was last October. Liberty Bell 7 was not lost, — it was at the Adler Planetarium!

I know the Adler's advertising people mean well, but let's be realistic. Given its location at the end of a peninsula jutting more than 1,500 feet out into the wind-swept waters of Lake Michigan, the planetarium isn't a place most people stumble upon by accident. Excepting those who go there to fish, people go there fully intending to enter the building, whether posters cover the exterior or not. Surely, the few stray tourists that might be swayed by the banners to pay an impromptu visit is so small that the admission fees they surrender wouldn't cover the cost of banners themselves.

Instrument Panel of Liberty Bell Seven

Liberty Bell 7 was a Wunderkind of science and American industry, and no one can argue that it shouldn't be preserved for future generations who will doubtless one day marvel at our generation's accomplishments, but what connection has this machine to astronomy? Why is it at the Adler when it clearly belongs at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry?

The Zeiss Projector

The Zeiss projector was the heart and soul of the Adler Planetarium. Devices like this one are still the means by which those with a desire to learn about astronomy often take their beginning steps on the road to their own, personal "first light." Second only to optical telescopes in revealing the wonders of the heavens, this projector possess the capacity to demonstrate one feature of astronomy that no other technology can: the movement of celestial bodies across the sky, as seen from anywhere on earth, over a course of time that can range from as little as a few minutes to as much as thousands of years — all in the course of just a few minutes. It can display the full expanse of the night sky, and can show it as it would appear to the human eye on a clear, dark night, free of dust, smoke, and other, man made pollutants. Few city dwellers have ever seen the sky in all its splendor, and to this day people still audibly gasp when the Adler's Zeiss projector reveals that breathtaking sight to them for the first time. Most important, it can do all these things with the flexibility needed so that a lecturer can interact spontaneously with his or her audience.

I was also troubled to discover that the seats in the planetarium chamber were considerably less comfortable than those in the Adler's more recent addition, the "StarRider" theater. In the "StarRider," I found, things are expected to explode and burn with frequent regularity, often under the direction of thrill seeking audiences frantically pressing electronic, chair-arm buttons in an effort to "interact" with the scheduled cosmic cataclysm of the month. It would appear that to accomplish this worthy goal, comfortable seating was deemed a high priority.

At first I was disappointed, even angry. It seemed to me that the Adler had allowed itself to be seduced by soulless, corporate bean counters incapable of appreciating the value of anything other than the "bottom line." Perhaps to some extent that's true. However, it may be unfair to place all of my disappointment at the Adler's doors. After some reflection I'm inclined to suspect that, like this country's other planetaria, the Adler has simply fallen upon hard times. Like them, it may no longer be able to depend only upon educating those with an interest in astronomy for its survival. People of the present generation appear to be different from those of mine. They don't seem interested to know why Venus is never visible in the night sky at midnight, aren't at all curious as to why the spectra of distant stars shift to the red, don't find the stars themselves to be of any interest. They want to have "fun." They need to be entertained. They want to see Bruce Willis explode and burn, and at the Adler, they demand such experiences on a cosmic scale — with a joystick!

Have I been fair in my criticism of the changes I found? It's hard to say. No one knows how many young people were positively influenced by the Adler in the past. No one can say how much good society derived from the fine work it did back then. But, no one can deny that the Adler of today is no longer what it was, and that its philosophy has changed. As a youth, I saw the Adler as a shrine dedicated to learning about astronomy. To me it was a cathedral where one could silently ponder the mysteries of the universe and contemplate his or her own, small place within. That's clearly not the case today. Now, it has a character much more like that of an amusement park. It has become an unfit place to meditate, a poor place to pray. It appears moneychangers have once again taken over a temple.